At dawn, the Omo Forest comes alive with a cacophony of whispers. Giant mahogany trees are blurred into a soft cloak of mist, with the melody of chirping birds emerging from the morning fog. Somewhere deep in the forest, some of the last herd of elephants in southwestern Nigeria quietly map the damp soil with their feet.

But the calm is deceptive. Omo Forest Reserve, a 1,305-square-kilometer protected area in Ogun State, is under siege. Chainsaws snarl in the distance. Cocoa farms spread like wounds through the undergrowth. Timber trucks rumble down bush paths carved illegally into the reserve. And poachers, emboldened by weak enforcement, leave behind snares, gun shells, and fear.

Here, Nigeria’s last forest elephants are forced to the brink.

Amid this crisis stands one man, Emmanuel Olabode, a conservationist whose life has become entwined with the fate of these elephants. For nearly a decade, he has walked the forest, tracked the animals, recruited rangers, and tried to reconcile communities with conservation.

The ranger who cares

“When I first heard about elephants in Omo, I didn’t know they were so close to Lagos,” Olabode recalled, his voice carrying both awe and disbelief. “It took months of following footprints, droppings, broken branches, signs everywhere, but no actual sighting. When I finally saw them, it was one of the most intriguing moments of my life.”

As project manager of the Forest Elephant Initiative at the Nigerian Conservation Foundation, Olabode leads a small team of 12 rangers tasked with protecting Omo’s fragile wildlife.

“We use the elephants as a flagship species,” he explained. “If we can save them, we can save everything else here, chimpanzees, monkeys, birds, even the trees themselves.”

But elephants are only a part of the story. Omo shelters over 200 tree species and more than 100 types of mammals and birds, from the rare Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee to the endemic white-throated guenon monkey. Each faces the same fate: survival or vanishing, determined by how quickly the destruction of Omo is curbed.

“Biodiversity is a critical part of our work,” Olabode explained. “We are losing species that once defined this forest. Some are so rare now that even researchers spend years without spotting them.”

A forest under siege

Driving into Omo Forest is like stepping into two colliding worlds. On one hand, towering rainforest trees soar above all else, their buttresses anchoring the soil. On the other hand, yearning gaps reveal scars of human invasion, fresh tree stumps, charred earth from slash-and-burn farming, and makeshift camps of loggers.

Officially, Omo is designated a Strict Nature Reserve, a classification that should bar extractive activities. In reality, illegal timber harvesting and subsistence farming flourish, threatening the integrity of the forest. Over the years, seven percent of its tree cover has been lost, a number that underestimates the intensity of ongoing degradation.

Olabode’s rangers routinely encounter poachers and illegal loggers, sometimes armed and aggressive. “It is dangerous work,” he admitted. “Some of them will attack anything that comes their way. We also deal with human-wildlife conflicts when elephants raid farms or when farmers encroach deeper into elephant habitat. Every day is a struggle.”

The risks are compounded by the terrain itself: rangers trek for hours through rivers, hills, and thick undergrowth, often in torrential rains. “This is not like working in a zoo where animals are behind fences,” Olabode said. “Here, we share the same space with them.”

Turning poachers into protectors

Perhaps the most striking shift in Omo’s story lies in the men who once hunted its wildlife but now stand guard over it.

For instance, Gbenga Ogunwole, a wiry man with a ready smile, hitherto spent years hunting antelope and monkeys to feed his family. Today, dressed in a faded ranger’s uniform, he patrols the forest alongside Olabode.

“World Ranger Day is meaningful to me,” Ogunwole said. “Before, I was part of the problem. Now I’m part of the solution. People now recognise our work — to protect nature instead of destroy it.”

By recruiting former hunters as rangers, the Forest Elephant Initiative not only reduces poaching but also integrates local knowledge of animal behaviour and forest navigation into conservation. This approach has also improved relations with nearby communities, who once saw rangers as outsiders threatening their livelihoods.

“We regularly visit villages, talk to people about why conservation matters — not just for animals, but for human life,” Olabode explained. “When they see their own brothers wearing the ranger uniform, it changes the narrative.”

Between Farmers, Loggers & Elephants

Still, the battle for Omo is as much economic as it is ecological. Farmers cultivate cassava and cocoa deep inside the reserve, while loggers, some backed by powerful syndicates, target prized hardwoods like mahogany. Both groups argue they rely on the forest to survive.

“Everybody claims the forest is theirs,” Olabode said. “The farmers say they must feed their families, the loggers say they need timber for their business. But where do the elephants go if we lose the forest?”

The result is frequent tension. Rangers are caught in the middle, enforcing conservation laws that are often undermined by weak prosecution and political interference. Arrested loggers or poachers sometimes walk free, eroding ranger morale.

“Our work will only succeed if policies are enforced,” Olabode insisted. “If offenders are arrested and prosecuted, it will deter others. Right now, too many cases end with nothing.”

The farmers’ perspective is layered

In J4, a settlement inside the reserve, cocoa trees line the forest edges in neat, cultivated rows. For thousands of farmers, cocoa is life.

Akeji Femi, former public relations officer of the Association of Cocoa Farmers in J4, has lived here since 1995.

“There had been no incident of elephants attacking humans,” he said. “There was already cocoa farming by the time I got here.”

Akeji Femi, a former Public Relations Officer of the Association of Cocoa Farmers

For Femi, farming in the reserve is not theft but survival. He described a system where farmers, many of them migrants, pay multiple levies to gain access to farmland.

“We pay money to different community chiefs to get land. In 1995, we paid N5,000. Now, in 2025, it is N100,000. Then we pay to government more than N13,000 per tonne of cocoa. We pay the state Ministry of Agriculture. Most of us are visitors in these communities. We don’t fight for land. We stay where we are given.”

For him, the solution lies not in conflict but in clearer land use policies. “What I recommend is for the government to give us a portion to do cocoa farming, while they can also set another part for forest preservation,” he said. “We know there are parts set for the elephants which we don’t go to.”

On paper, this sounds simple: zoning the forest to balance agriculture with conservation.

In reality, blurred boundaries, weak enforcement, and political interests make it far messier. Farmers often find themselves encroaching into restricted zones either knowingly or unknowingly, while rangers struggle to enforce rules without appearing hostile to communities who feel they have paid their dues.

But while cocoa farmers defend their presence, others accuse them of being a greater threat to the forest than anyone else.

Odunayo Ogunjobi, a timber contractor licensed by the Ogun State Ministry of Forestry, has watched with alarm as swathes of economic trees are felled to make way for cocoa plantations.

“The government generates as much as over N8 million from me alone,” Ogunjobi said, “excluding the other indirect workers who depend on me. But illegal cocoa farmers are destroying the forest. They cut down valuable economic trees in Omo’s J4 area just to pave way for cocoa farms.”

Odunayo Ogunjobi

He recalled that during the administration of former governor Gbenga Daniel, illegal farmers were expelled from forest reserves across the state. “As soon as Daniel left office in 2011, they all returned and increased in numbers,” he said, his frustration clear. “Now they pose a great threat to the security and economy of the state.”

For Ogunjobi and other contractors, the issue is not just about wildlife, but also about the sustainability of the timber industry itself.

“We are struggling to get timbers because most of the illegal contractors are taking over everywhere,” he said. “We generate a lot of revenue for the government, but no one seems to be listening to our cry. No one is monitoring the forest. At this rate, in the next two or three years, the trees or forests will go extinct.”

Paper trail

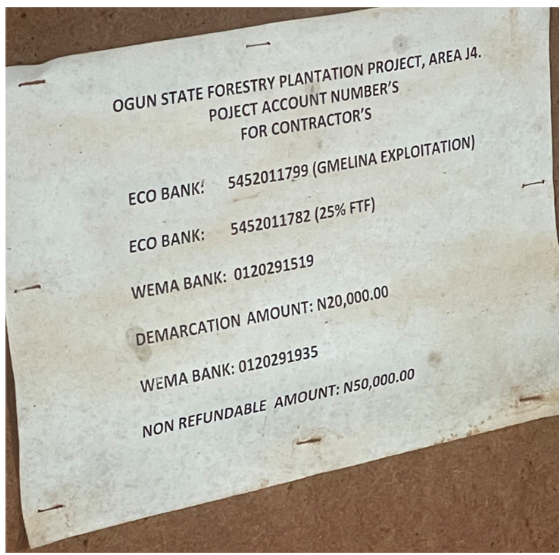

Evidence of the state’s deep financial entanglement in the forest economy is captured in a document pinned on a wall at Area J4: “OGUN STATE FORESTRY PLANTATION PROJECT, AREA J4. PROJECT ACCOUNT NUMBERS FOR CONTRACTORS”.

The notice lists official bank accounts for payments tied to different forestry activities: Eco Bank 5452011799 – for Gmelina exploitation; Eco Bank 5452011782 – for 25% FTF (Forestry Timber Fee); Wema Bank 0120291519 – demarcation amount of N20,000 and Wema Bank 0120291935 – a non-refundable amount of N50,000.

The structured fees, covering exploitation, levies, demarcation, and administrative charges, reveal how forestry exploitation is not only permitted but institutionalised by the state. Contractors, like Ogunjobi, pay millions into these accounts. But cocoa farmers also pay chiefs, ministries, and additional levies, creating a dual system of extraction.

This fragmentation of authority means that while the state can claim legitimacy through bank receipts, farmers can also claim legitimacy through receipts from chiefs and agricultural ministries. The result is overlapping rights and competing claims to the same forest — a recipe for conflict and unsustainable exploitation.

The Global Ranger Crisis

Omo’s challenges mirror a larger crisis across Africa. With human populations expanding and forests shrinking, rangers are the thin green line between survival and extinction for countless species.

“Rangers are nature’s first line of defense,” said Linus Unah, West Africa Director for Wild Africa. “Without them, our iconic wildlife like lions, elephants, and gorillas could disappear forever.”

Yet, beneath the passion lies sacrifice. Rangers spend weeks away from their families, exposed to harsh weather, loneliness, and sometimes hostility from their own communities.

“Some rangers are ostracised because they arrest neighbours or relatives involved in illegal activities,” Unah explained. “It takes resilience and dedication.”

Globally, the mental toll of ranger work is only beginning to be recognised. Exposure to violence, animal attacks, and isolation often leads to trauma. Without support systems, many rangers suffer in silence.

“People celebrate us once a year on World Ranger Day,” said Ogunwole, the former hunter. “But for us, every day is ranger day. We wake up not knowing what we will face.”

Yet, rangers remain under-resourced. Globally, there are an estimated 280,000 rangers, a fraction of the 1.5 million needed to protect 30 percent of the planet’s land and sea by 2030. Between 2006 and 2021, more than 2,300 rangers died on duty worldwide, 42 percent from criminal activity linked to wildlife crime.

For Omo’s team, the lack of insurance, medical care, and protective equipment compounds the dangers. “Rangers also have families, they have dependents,” Olabode said. “They deserve life insurance, healthcare, and proper motivation. Without that, the risks are enormous.”

The human cost of conservation

Yet, beneath the passion lies sacrifice. Rangers spend weeks away from their families, exposed to harsh weather, loneliness, and sometimes hostility from their own communities.

“Some rangers are ostracised because they arrest neighbours or relatives involved in illegal activities,” Unah explained. “It takes resilience and dedication.”

Globally, the mental toll of ranger work is only beginning to be recognised. Exposure to violence, animal attacks, and isolation often leads to trauma. Without support systems, many rangers suffer in silence.

“People celebrate us once a year on World Ranger Day,” said Ogunwole, the former hunter. “But for us, every day is ranger day. We wake up not knowing what we will face.”

Nigeria’s Forgotten Elephants

Elephants once roamed widely across Nigeria. Today, fewer than 400 are thought to remain in scattered pockets across the country, from Yankari Game Reserve in Bauchi to Okomu National Park in Edo. Omo Forest may hold fewer than 100, perhaps Nigeria’s last viable forest elephant population.

Forest elephants play a critical ecological role. By feeding on fruits and trampling vegetation, they disperse seeds and open pathways that allow forests to regenerate. Scientists call them “gardeners of the forest.” Losing them would unravel Omo’s ecological fabric.

But Nigeria’s elephants have long been neglected in conservation planning. International headlines often spotlight East Africa’s savannah giants, while their forest cousins fade in obscurity. For Olabode, this invisibility makes the struggle harder.

“If elephants disappear from Omo, Lagos will be the only megacity in the world with elephants at its doorstep that failed to protect them,” he said quietly.

A ray of hope

Despite the odds, Olabode insists the fight is not a losing battle. Awareness campaigns have begun to shift community attitudes, and government officials have shown renewed interest in supporting conservation.

“We are making progress, even if it is slow,” he said. “With government support and stakeholder collaboration, we can secure this forest.”

Wild Africa, alongside Nigerian Conservation Foundation, is pushing for stronger laws, ranger support, and integration of conservation into national planning. “It requires political will,” Olabode stressed. “Government must act before it is too late.”

For rangers like Odamo Yemi, the work is deeply personal. “I love to protect nature, and I love to watch animal behaviour,” he said. “Even if it is risky, it is worth it.”

What is at stake

The fate of Omo’s elephants is not just about wildlife. The forest provides clean water, carbon storage, and climate resilience for millions in southwestern Nigeria. Its loss would accelerate flooding, soil erosion, and heat extremes in a region already grappling with climate shocks.

“Protecting elephants means protecting people too,” Olabode said. “If the forest is gone, where will we go?”

As dusk settles over Omo, the forest hums with cicadas and distant birdcalls. Somewhere in the shadows, the elephants move quietly, their survival balanced precariously between conservation efforts and human pressures.

For now, the rangers keep watch, weary but undeterred. Their fight is for elephants, for Omo, and for a future where Nigeria’s last giants are not forgotten.

This article was produced in partnership with Wild Africa. It was first published on www.businessday.ng