One of the pangolin’s features that makes it the most illegally trafficked mammal in the world may also be one of the most important features to save it from poachers, a new research is suggesting.

Wildlife forensic experts have figured out a way to lift fingerprints from pangolin scales. The new method uses gelatin, a common way that forensic scientists pick up prints from surfaces.

The new research involved an international collaboration between United Kingdom researchers and wildlife crime rangers based in Africa and India. Paul Smith, director of the Forensic Innovation Center at the University of Portsmouth and his colleagues describe the method in a recently published online paper included in the August edition of the journal Forensic Science International.

Eight pangolin species live in Africa and Asia. All of them are considered threatened — their status ranging from vulnerable to critically endangered. The animals are hunted for their meat and scales and are the world’s most trafficked animal. In June, Chinese officials removed pangolin scales from a list of approved ingredients used in traditional medicine in an effort to deter pangolin hunting, killing, and smuggling.

At the start of the Covid-19 outbreak, pangolins were thought to be a potential interim animal host, facilitating the spread of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 from bats to humans. Now, that theory is largely discounted, and pangolins are being studied as a potential treatment model since the animals’ unique immune system prevents them from getting very sick.

Read also: Pangolins being wiped out at terrifying rate

Gelatin which is capable of picking up microscopic prints from materials has been used in forensics for around a century, Smith revealed. Its basis is simple: When something touches a surface, it may leave behind an impression — perhaps in the dust, or in the form of a sweat deposit.

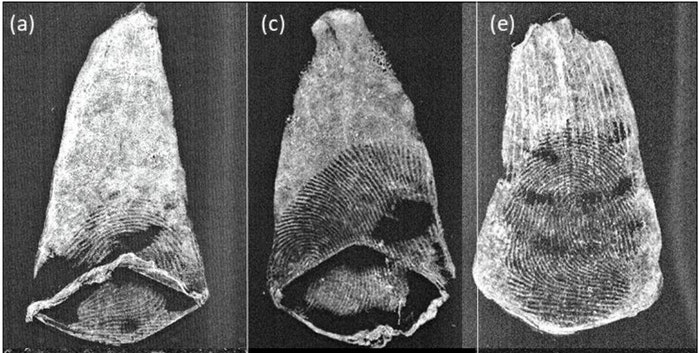

By pressing a sheet of gelatin onto the surface, the gel — a soft material, which can be cut to different sizes but looks similar to the underside of a mousepad — adheres to the surface and picks up those impressions. That’s true whether the surface is a tabletop or a pangolin scale.

“You will see it more or less instantly,” Smith said.

Since gel picks up other substances besides fingerprints, it can give scientists additional clues into where pangolins are being traded. By lifting soil or pollen, for example, which are specific to certain regions of the world, forensic experts can detect where a pangolin scale has traveled.

For that reason, using gel is a better option than the old standby of dusting for fingerprints, Smith noted.

“When you apply powder to something, potentially, you’re brushing things away,” he said. “You’re taking away the evidence.”

It also helps that pangolins are adept at digging and burrowing, so they’re likely to pick up some debris from their surroundings.

In future gelatin could even be used to pick up DNA, the director added

“Gel is not only just for finger marks,” Smith said. “It can potentially be used for a whole host of evidence opportunities” on scales and other items.

Beyond pangolin scales, the method could hypothetically be used for other smooth surfaces, like ivory tusks. It’s particularly useful for pangolins because scales are small enough to efficiently check for fingerprints.

Using gelatin could also help keep people safe when they are tracking down poachers. It’s low-tech, easy to use, and allows wildlife rangers to quickly get in and out of a scene, Smith explained.

That’s important because illegal wildlife trade is a dangerous realm — especially for those trying to stop it. A 2018 study found that more than 100 wildlife rangers died in the line of work in just one year. Of those deaths, 48 people were murdered while working.

Hearing what it’s like to work on the ground in places where pangolin trade is thriving helps illuminate how science can help, he said. The key, he says, is to “develop methods that work — that’s based on the lens of people doing the frontline investigation.”

That means traveling internationally and talking to local rangers about their experiences.

“Allow the design, the development, the methods that work to come from those at the frontline,” Smith added. “Those that experience it day-in, day-out. Those that know the area.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.